Printing Technology

September 15th, 2009

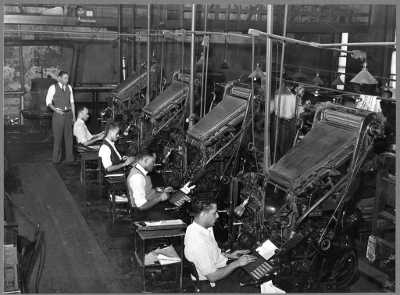

Linotype operators of the Chicago Defender by Jack Delano, 1941. From the FSA-OWI Collection at the U.S. Library of Congress (the picture is in the public domain)

Linotype machines and rotary printing presses were the main innovations in printing technology during the XIX century. The price of a printed publication was significantly lowered, an this allowed a broader access to books and newspapers, as well as the flourishing of new independent publications. In my current research on the work of Uruguayan modernista Roberto de las Carreras, I can appreciate the importance those new printing technologies had for the establishment of an anarchist press and a series of editorial projects known as Bibliotecas populares, which were key in the diffusion of socialist ideas at the end of the 19th. century. One of the major editorial projects of that time was the Sempere publishing house in Valencia. This house published the firsts Spanish translations of Karl Marx, Michail Bakunin, Piotr Kropotkin, and other revolutionary as well as liberal thinkers. The books were sold at a extremely low price (one peseta) and were widely read not just in Spain (where they were originally published) but also in Latin America (I still have some of those books that belonged to my grandfather).

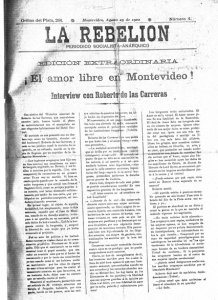

The network built by the internationalists was used by Sempere to reach a wider public. But this network can be appreciated also in local socialist and anarchist newspapers: their correspondence sections were a truly international tribune were socialist and anarchists around the world confronted ideas and coordinated actions. The newspaper La rebelión, which lasted one year (from 1902 to 1903), hosted in its pages a wide range of contributors from Europe and Latin America. Through an economy based in bartering and gift practices, the newspaper editors were able to host in its pages hotted debates where the names of Kropotkin or Élisée Reclus could be seen side by side with a local anarchist baker such as Joaquín Barberena. Anarchists were able to establish their own spot in the cultural realm as holders of the necessary know-how to use the new printing and other graphic technologies (photography starts to become widely available at this time too). Beside printing technologies, advances in transportation contributed to the speed of communications, allowing the editors of La rebelión to send the newspaper to Europe and the Americas, and vice-versa.

La Rebelión. August 25, 1902, announcing the arrival of free love in Montevideo.

The debates on free love that took place between 1902-1903 in this newspaper are a good example of such interaction. It was a debate that started as a local discussion held in Uruguay, aroused by the intervention of Roberto de las Carreras, who promoted his own example of free love practice. Soon interventions from Buenos Aires started to appear. In 1903, the intervention from Émile Armand (whose real name was Ernest-Lucien Juin, one of the main advocates of free-love in the first half of the 20th. century, and author of La révolution sexuelle et la camaraderie amoureuse) from France, calls for the creation of a new libertarian community based on the past experiences of the Icaria and Cecilia colonies that existed in the XIX century in the U.S. and Brazil. The debate doesn’t continue because the newspaper is shut down by the police. In the last issues, the changes in the addresses of the printing press facilities evidence the legal troubles the editors were facing. The question that I was asking myself when collecting this data at Uruguay’s National Library last summer was what can we learn from the way these local publishers managed to create such networks, that allowed for a transcontinental cultural exchange bonded by a common political practice. The way they quickly appropriated the new technologies of the time could be seen as an example from which to learn possible practices for the use of the new technologies available to us today.

Leave a Reply